“I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

William Blake, ‘London’

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.”

Are we really so miserable? We: the proletariat, ‘the great unwashed’—the working class. William Blake (see ‘London’, above) seems to think so—his walk through 18th Century London is an all-expenses-paid trip to misery town. Likewise for Henry Lawson’s ‘Faces in the Street’: “I look in vain for traces of the fresh and fair and sweet / In sallow, sunken faces that are drifting through the street”. Personally, iamb not so dour, but it’s a fact well-recognised that, historically, the situation of the working class has been a bit shit. Poetry has done its best to represent this situation: whenever you read a poet described as ‘revolutionary’, ‘radical’ or ‘seditious’, they’ve probably stuck their head out for the proles and got a good smack for it—even Mr. ‘White Man’s Burden’ Kipling copped ‘seditious’ for his poem, ‘Ulster’.

Of course, the biggest smack always comes to the workers who rise up. Take the Easter Rising of 1916. Irish Republicans revolted against their British occupiers and were utterly, mercilessly put down for it. Google the North King Street Massacre for your bedtime story tonight and for the tip of the iceberg. The direct issue here was a colonial one: salt and pepper, England and oppressive imperialism—that sort of thing. Most colonial issues are linked closely with class struggles (as is the history of all hitherto society), and I like W.B. Yeats, so pay attention!

Yeats’ ‘Easter 1916’ poem addresses the rising, and it vacillates between admiration for the rebels and criticism of Britain’s response, in particular reckoning that everything now is different: “All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born”. Note the oxymoron: Yeats writes in another poem “Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone”. He thus questions whether the deaths were needless, as England might have granted Ireland its freedom without the rebellion. In any case, Yeats understands enough to eulogise a worker who stands up, heedless of what they actually effect: “We know their dream; enough / to know they dreamed and are dead”.

The quote in the title of this article comes from ‘He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven’, another of Yeats’ that deals primarily with love, but divorced from its context it too is evocative of the working class experience. What is there but dreams? Have them and die. So next time you see your boss, square up and say: “I have spread my dreams under your feet; / Tread softly because you tread on my dreams”. It’ll be the start of something, I promise.

Irish poet Eiléan Ni Chuilleanáin remembers, writing into the middle of the rising, her grandparents’ experience:

“Everything in the room got in her way,

the table mirror catching the smoke

and the edges of the smashed windowpanes.

Her angle downward on the scene

gave her a view of hats and scattered stones”.

This look at the 1916 rebellion was Chuilleanáin’s way of confronting the Troubles. It’s also a family affair: her great uncle was a rebel leader who was unjustly executed.

Closer to home, Henry Lawson’s poem ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’ commemorates the 1891 shearers’ strike, often attributed as a factor leading to the ALP’s foundation. The politics around this is messy: along with better pay and protections, the workers demanded the exclusion of low-cost Chinese labour, an attitude manifest in the White Australia Policy a few years later. Rather than advocate for better rights for the Chinese workers as well, the Australian workers wanted them out: no solidarity across the colour line. Although Lawson’s poem doesn’t engage with these racial concerns, read as something of its time it’s actually

quite metal:

“So we must fly a rebel flag,

As others did before us,

And we must sing a rebel song

And join in rebel chorus.

We’ll make the tyrants feel the sting

O’ those that they would throttle;

They needn’t say the fault is ours,

If blood should stain the wattle.

And yes, he (Henry Lawson) was accused of sedition. The government presumably referred their wattles nice and clean, not dirty and a symbol for revolution.

“Out damned spot! Out, I say!”

The Australian Government, in reference to their ‘wattles’.

Suffrage, too, is tied up with class conflict. A core understanding of the intersection between Marxism and Feminism is that capitalism relies on women as domestic unpaid labour, in addition to women as workers, to function. For dinner, ladies: a hot plate of oppression with a side of oppression. Guess what! Oppression for dessert, too. Suffragette Helen Todd challenged this situation across many protests. In particular, a speech she gave included the line, “bread for all, and roses too”; this inspired the title of James Oppenheim’s poem ‘Bread and Roses’.

“As we come marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill-lofts gray

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing, “Bread and Roses, Bread and Roses.”

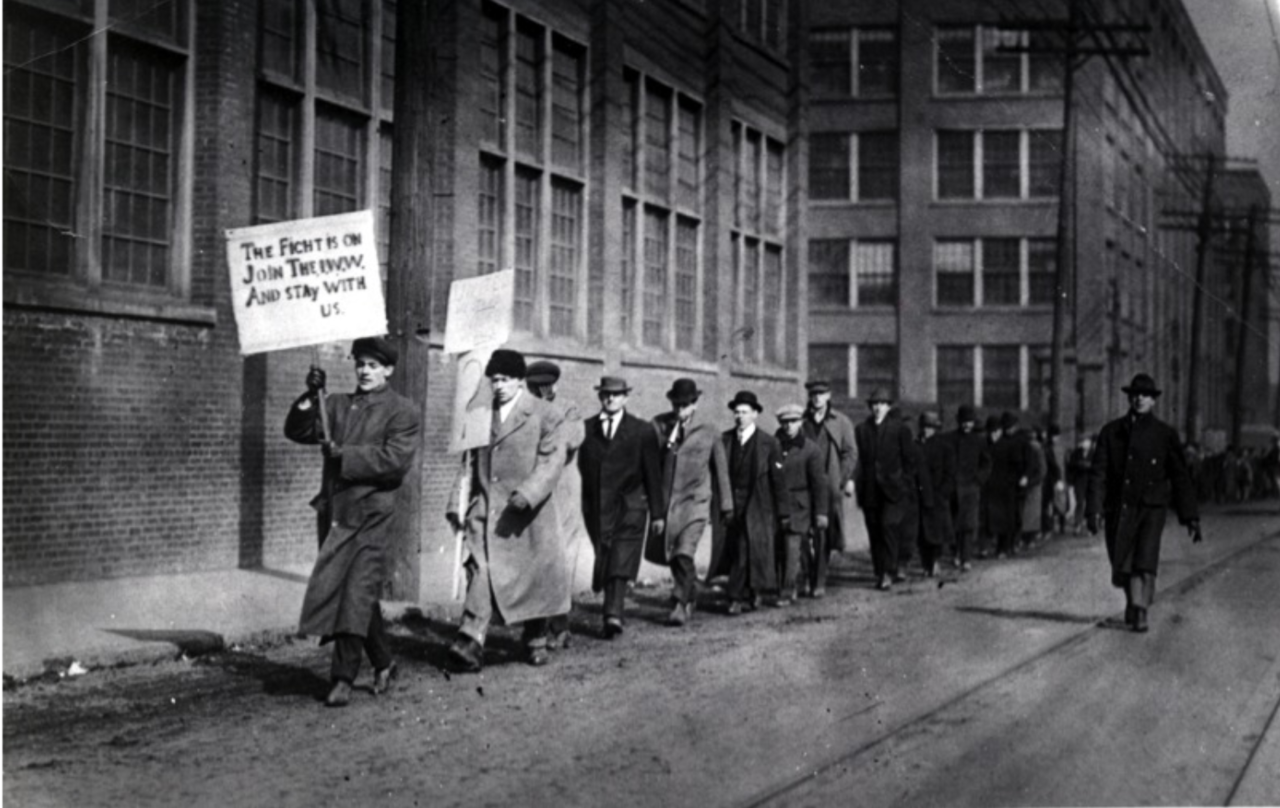

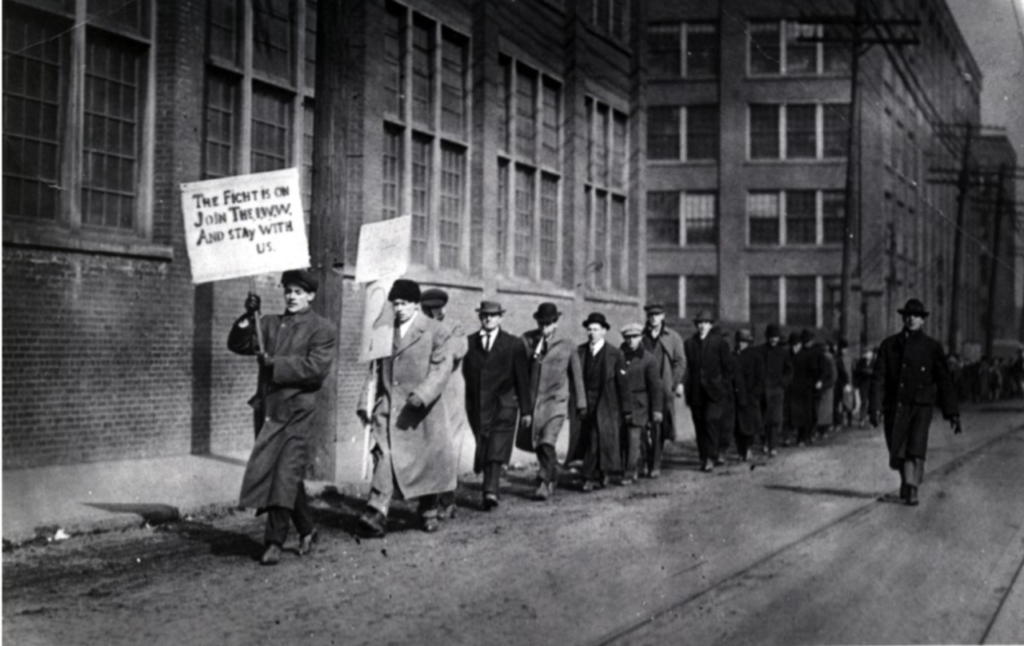

This phrase also gave its name to a successful 1912 textile strike in Massachusetts, notable for being for the rights of immigrant workers, and comprising largely female and ethnically diverse workers. It’s a phrase that sticks with you, evoking not just the usual cries of the working class—better conditions, pay, food on the table—but burrowing deeper into class consciousness (and harkening back to Blake’s romanticism) with ‘roses’: there’s so much more to life than work. Have another stanza:

“As we come marching, marching, we battle, too, for men—

James Oppenheim’s ‘Bread and Roses’

For they are women’s children and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes—

Hearts starve as well as bodies: Give us Bread, but give us Roses!”

Before we all return to late capitalism, I’d like to drop a few more names that align with this tradition. I mocked Blake a little in this piece—he was a Romantic—but his ‘The French Revolution’ is a great anti-monarchist read. Martín Espada has long lamented the working class experience, with poems like ‘Vivas To Those Who Have Failed: The Paterson Silk Strike, 1913’. Chinua Achebe is known for Things Fall Apart, but was a cracking poet as well. Simon Armitage has written poems like ‘Those Bastards in Their Mansions’ that express in lovely, flowery terms how to feel about the rich. Maya Angelou and Gwendolyn Brooks both wrote poetry at the intersection of civil rights and workers’ rights and Walt Whitman’s advocacy for workers in his journalism can be felt in his poetry.

There are so many more poets I could put in this section, especially poets from minorities, who, as in every field, have been marginalised in the canon.

So, to conclude, poetry’s fucking great, you should read it, and vive la révolution.

Wait, was this seditious?

Tom Lewis

Views: 179