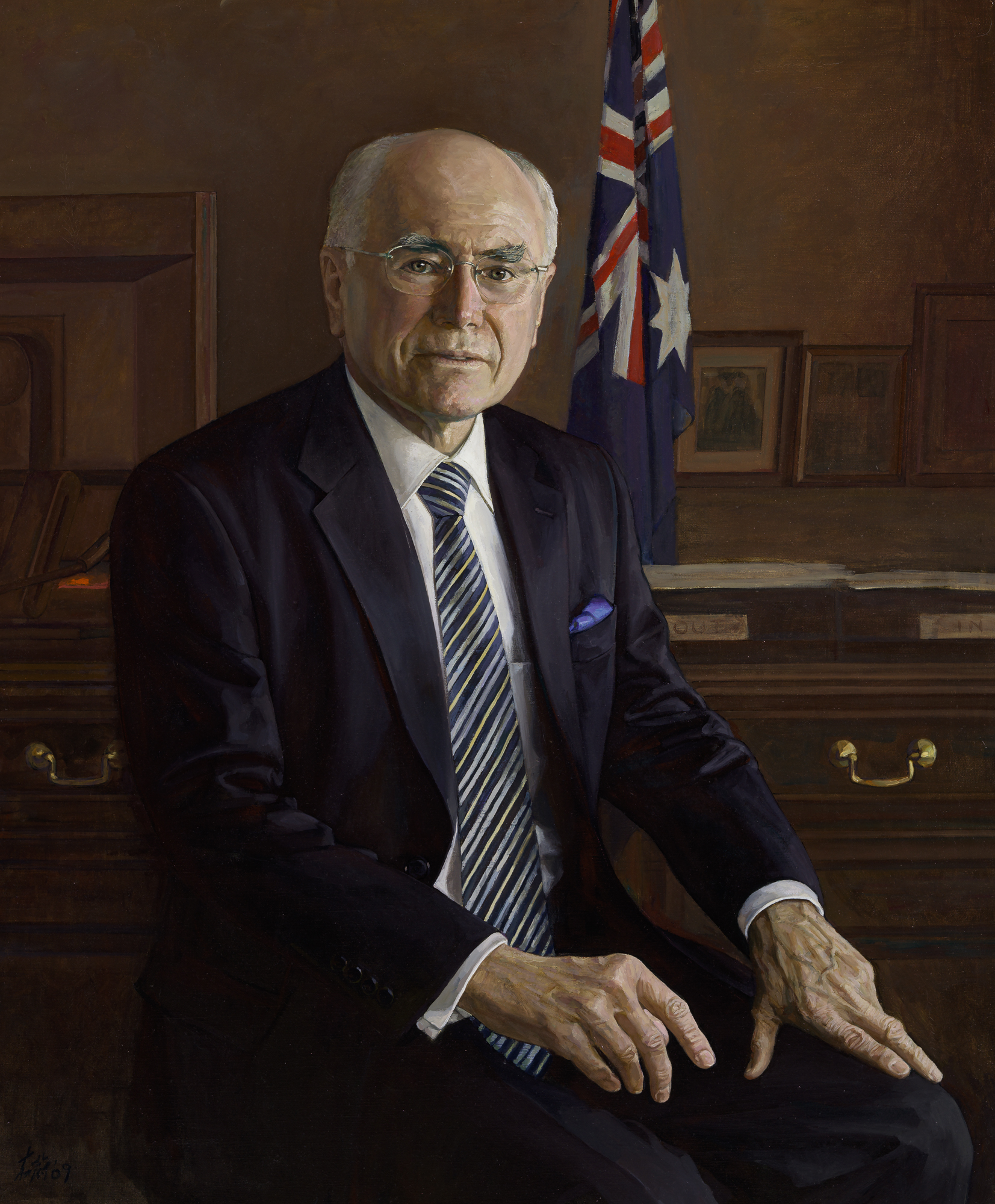

Conservative, cautious and committed – three words that summarise John Howard’s political style. Electorally popular in his day, controversial amongst progressives and leaving behind a debated policy legacy, some argue that John Howard is one of, if not Australia’s best prime ministers, whilst others contend that his legacy is one of intergenerational wealth inequality.

Having just finished his autobiography, Lazarus Rising, I’d like to explore the philosophical underpinnings of John Howard’s approach to governance, a contrast to my recent article on Paul Keating’s vision for Australia.

If Paul Keating is a social democrat who embraced free-market reform, John Howard is an interesting blend of economic liberalism and social conservatism. With an emphasis on individualism, reason, tradition, respect for authority, incremental reform, and Protestant-Christian values, he is a far cry from the left-leaning political ethos on campus. Controversially, he opposed same sex marriage, refused an apology to the stolen generations and argued “multi-culturalism is not our national cement.”

An interesting aspect of the conservative school of thought, driven by thinkers such as Edmund Burke, is their belief that humans are inherently flawed – that they crave security and are wary of the unknown. Howard’s gun reforms following the Port-Arthur massacre are a reflection of this. Unlike our American cousins, Australians are willing to give up certain individual rights if it means we can sleep easily at night. In a broader context, this opens an interesting Australian duality – that we take pride in the rebellious, lawless jolly-swagman archetypes, while also having some of the strongest legislation in the context of public safety (not many other countries fine you for not wearing a helmet!). This bleeds into what Howard refers to as our ‘Celtic scepticism’ – an imported Australian suspicion of change, and he used this to his advantage.

Whether it be in the defence of the monarchy, our unquestionable alliance to the US, or the refusal to allow the Norwegian freighter the MV Tamper, carrying 433 rescued refugees to enter Australia, Howard’s philosophy of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ saw much electoral success. In an interesting parallel to our current Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, Howard was seen as ‘a safe pair of hands’ during uncertain times.

Foreign policy dictated the second half of the Howard government. Being present in Washington during the September 11 attacks, Howard invoked the ANZUS treaty, marking the first and only time Australia had done so. Australia also led an international peace-keeping effort in East Timor, an echo of the wider ‘top-down’ liberal peacebuilding effort globally. Although in response to the UN, he claims “we should be wary of giving unqualified assent to the dictates of multilateral bodies whose rules are written sometimes by majorities which include nations neither believing in nor practising the rule of law.”

The ideological adoration for liberal peacebuilding saw less success domestically. In 2007, the Howard Government enacted the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Bill in response to the Little Children are Sacred Report, which exposed widespread child sexual abuse in remote Indigenous communities. Notably, the report championed the need for culturally appropriate, community-led solutions that focused on prevention and not just enforcement. Indicative of a classic top-down approach, months after the report’s findings, the Australian Defence Force was on the ground enforcing harsh and punitive policies on communities – an eerie shadow of their previous operations in Afghanistan and Iraq just years prior. This policy was, by in large, a failure and has only worsened existing problems in remote First Nations communities.

Similar to Keating, Howard was booted out in a landslide victory after delving too far into his own personal ideology. He introduced Work Choices, a deeply conservative industrial relations policy that weakened unfair dismissal laws, restricted union power and allowed employers to bypass collective agreements and negotiate individual contracts with workers. It was deeply unpopular, and he even lost his own seat of Bennelong at the 2007 election.

Whether or not you are a fan of his policies, there is no denying that Howard was a successful conservative politician. Being the second-longest serving Australian Prime Minister, a lot of Howard’s sentiments are still felt today. With an ability to pivot toward centrist, pragmatic-driven polity, he was effective in painting an ideological roadmap for Australia – one driven through tradition, conservatism and an appeal to national unity. Dearly missed, better off forgotten or right for the times – Howard’s political tenure is an interesting one, and when approached from a place of curiosity, it helps us understand why Australia is the way it is today.

Written by Pat Franco

Views: 38