What does it mean to be Australian? A contentious question to put it slightly.

For a country of twenty-six million, the question of an Australian identity is blurred. Some argue the very fabric of our establishment is flawed – built on the dispossession of Indigenous people. Others argue that Australia has lost touch with its Anglo-Saxon traditions.

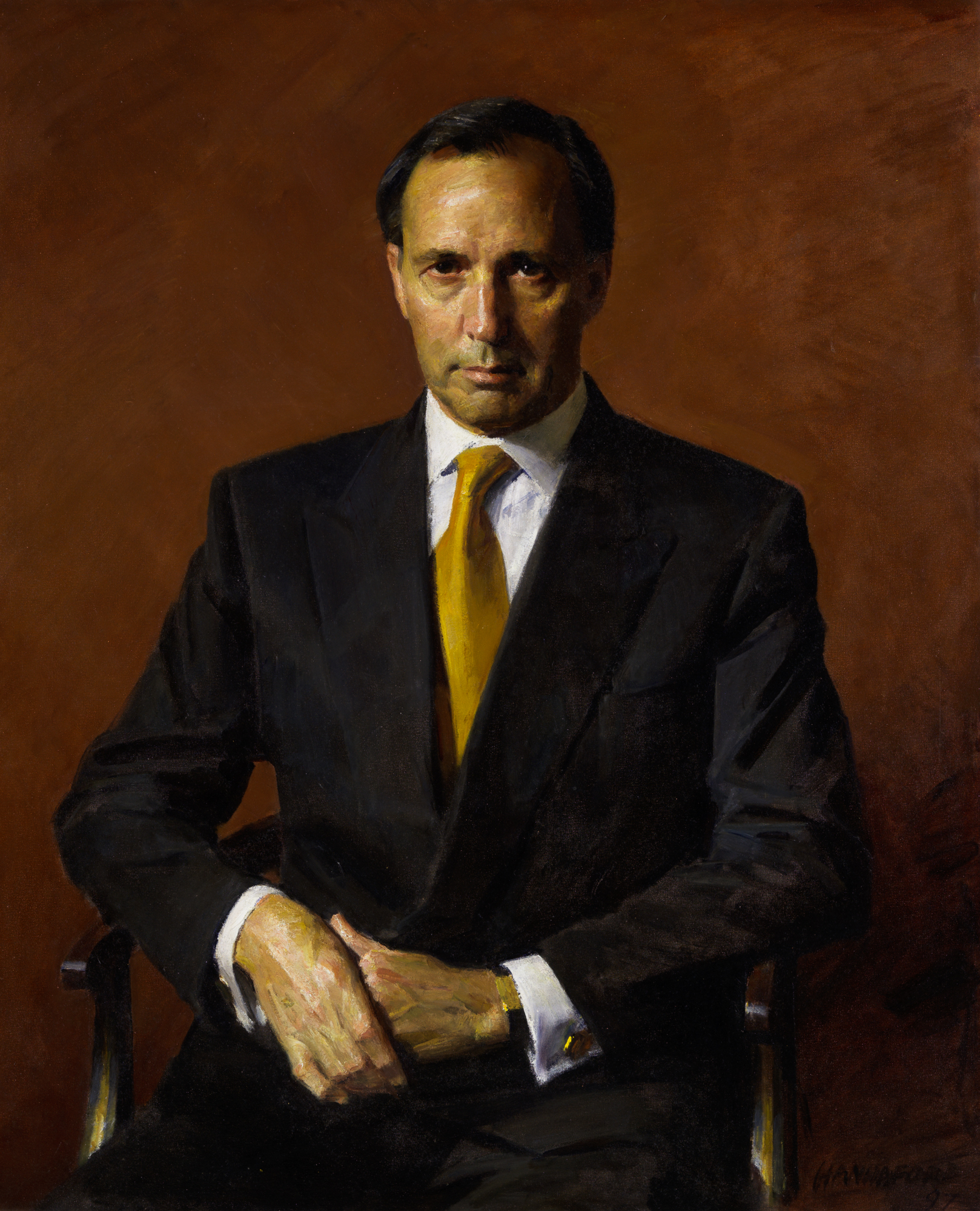

It’s an endless debate, and one I’d rather not get bogged down in. Instead, I’d like to highlight a unique vision of Australia envisioned by the former Prime Minister Paul Keating.

A reformer, polymath, economic rationalist and master of the political insult, Paul Keating is one of our most intriguing prime ministers. Not interested in sport, drinking beer or ‘tripping over news cables at the shopping mall’, Paul Keating aimed to tackle the big picture issues, as he describes, “making profound judgments about profound issues.”

Fundamental to his vision was an independent Australia. An “open, competitive, cosmopolitan country, which was a republic, and which was locked into the Asian construct.”

He was also the first prime minister to explicitly acknowledge the dispossession of Indigenous Australians in his now famous 1992 Redfern speech:

“We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life. We brought the diseases. The alcohol. We committed the murders. We took the children from their mothers.”

It’s important to note that Keating doesn’t believe guilt is a constructive emotion. Rather, he views the acknowledgment of historical truth, and commitment to improving the lives of First Nations people (reflected in policy such as Native Title), as a collective responsibility of all Australian moving forward – “goodness of heart and truth, is a necessary ingredient of a society with its head in the air.”

Keating is also critical of the way in which Gallipoli had been mythologized in Australian culture. Emphasising that this was a military defeat, largely at the hands of the British, he argues that the Kokoda campaign is better reflective of the modern Australian spirit. Moving beyond British influence, he articulates how Kokoda was fought by Australians in defence of our own sovereignty. Acting as a bedrock to an Australian republic, Keating criticises our knee-jerk dependence on Washington and London, believing Australia can be so much more, particularly in our own backyard of the Asia-Pacific.

Redefining Australia’s place in the world, viewing the arts as sustenance to the soul and reconciling with our Indigenous past are all very appealing things to a university student like myself. I acknowledge that not many other Australians would have the same appreciation. And in truth, Keating was decimated in the 1996 election, with John Howard winning 94 seats on a small-target platform, criticising many of Keating’s visions.

I reflect on the ‘realpolitik’ of winning elections. Many of these visions would be labelled as woke nowadays, like drinking from a poison chalice. Ultimately, Paul Keating was on an expedition to transform the national identity, but this quest lacked grassroots electoral backing. He was unable to resolve this conundrum. High idealism? Or a distinctive painting of Australia’s soul on a seldom touched canvas? I’ll let you be the judge.

Written by Pat Franco

Views: 36